Last weekend, Bee came down with a terrible cold. When she gets sick, we are clued in before she's even symptomatic by how clingy she gets. "I need you, Mama," she says over and over, trying to melt into my lap. The only way she could get any closer to me when she's feeling clingy would be if she unzipped my skin and snuggled in with my bones. I said that to her once and now she's always asking, "Where are your bones? I want to see your bones, Mama."

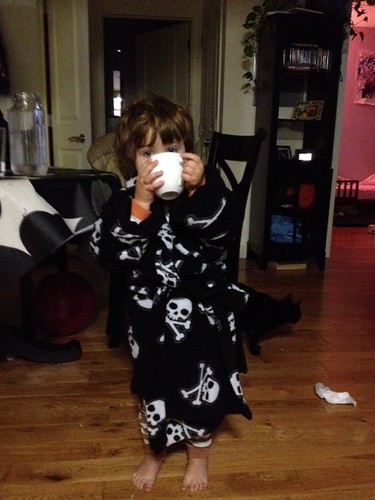

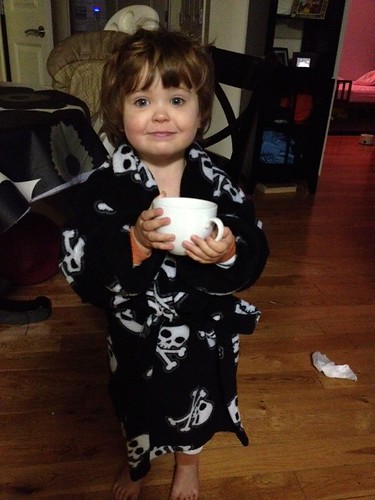

Soon she was milking it. Sick enough to stay home from school but just well enough to know how to get whatever she wanted from us by being both adorable and manipulative, she bundled up in a giant skull-print bathrobe and wandered around sighing and saying "Mama, I don't feel very well today." She and Johnny and Teeny piled up on the couch, watched lots of Sesame Street and read a zillion books (including Llama Llama Home with Mama, which our PT brought for her and which I recommend to any mama of sick kiddos). She went through so many tissues that her nose was angry and red. We glopped the Vaseline on her nose and the Vicks on her chest and she was in fairly good spirits about the whole thing. It helped that we made cupcakes and she started to drink tea like Mama. It was pretty cute.

It was cute, that is, until everyone else started to get sick too. By Monday morning, it was clear that Teeny was next. She barely made it through her morning OT and we canceled her PT, but she had a pediatric ophthalmologist appointment down in Tribeca that we could not reschedule. I didn't want to take a sick baby on the subway, so we all piled into the car. While Teeny and I were seeing the doctor, Thora took a badly needed nap and Johnny sat in the car with her, double parked, sipping coffee and reading a book.

I made this appointment for Teeny because I noticed that most other kids I've come across with cerebellar issues have poor vision. Many are farsighted and wear glasses before their first birthday. Others have had nystagmus or strabismus surgery in infancy. I didn't know what these things were two months ago, but now I wanted to rule them out. Teeny has big beautiful eyes that follow you wherever you go, and I didn't think there was anything wrong with them but I wanted to be sure.

A lot of people have asked me how an ophthalmologist can evaluate a baby's vision, so I will tell you. First, we talked about her diagnosis. He seemed completely unshocked, nodding his head as I related my concerns, which made me wonder about the patients he normally sees. Then he got to work.

He did three main things. One, he dimmed the lights and got out all kinds of toys with bright and flashing lights. He shook them, waved them up and down and from side to side and made noise with them to see if her eyes followed them. There were toys stationed in corners of the room, for example, a duck was perched up high on a shelf and it flapped its wings and squawked when the assistant flipped a switch. When Teeny looked up or over at any of these things, the doctor peered into her eyes with his little instrument, which had its own lights and Sesame Street stickers on it, so she wasn't bothered. Then he put drops in her eyes to dilate her pupils. She didn't love this part, so I nursed her while we waited a few minutes for it to take effect. Then another assistant used a hand-held version of the same machine that my eye doctor uses on mine to get a baseline assessment of her vision. As it zeroed in and made weird noises, the assistant sang Twinkle Twinkle Little Star and made twinkling stars with her hand. I'd say Teeny barely noticed the big metal Thing in her face. And finally, the doctor used the same toys he used at the beginning to have her look at him while he tested various lenses in front of each eye. Then he smiled and looked at me. "Perfect!" he said. "She's got perfect vision, and beautiful eyes." He paused. "A little therapy, and I betcha she'll be fine overall." I wasn't as optimistic, so I raced home and posted to the group about what the doctor said. Lots of parents reassured me right away. "I'd say you're in the clear," wrote one. When I saw that, I breathed a little more easily. I usually do trust doctors, but I sometimes believe moms a little bit more.

On Tuesday, I got a very exciting email. A week or so earlier, I'd sent a copy of Teeny's MRI images to a high school classmate of mine who is a pediatric neurosurgeon. I didn't want to bother him because I knew she was not a likely surgical candidate, but as it turns out, his mom and my aunt are best pals, so I was getting lots of pressure to reach out. I'm so glad I did, because he wrote me saying he presented her images at a departmental conference and they caught the eye of some experts. He connected me with a colleague of his who sent the images to a brain geneticist on the other side of the country who hypothesized excitedly that it could be some kind of genetic thing related to several specific proteins that he wanted to test for -- all WAY above my head. The possible diagnosis he cited is not even Google-able. I read the email chain a hundred times and looked up every word I didn't understand and I still have no idea what any of it could mean. But when I heard back from the colleague, he said he'd like to explore this on a research basis and that it could take a long time to figure out but that if anyone could, it's this fellow he knows on the west coast. I felt encouraged that someone was interested enough to really try to pinpoint what happened to her and what we can do for her. So we'll see what comes of that.

A day later, we had an appointment with a developmental pediatrician. This was approved and paid for by Early Intervention, but I didn't really know exactly what a developmental pediatrician was or what would happen when we saw her, so I looked it up. A developmental pediatrician is the kind of doctor who helps you determine a diagnosis of a developmental disability or test for specific developmental concerns. This doctor had a very strong reputation so I was glad to be seeing her, but we already had a working diagnosis, Congenital Anomaly of the Brain; or more specifically, cerebellar hypoplasia. So she and her team of pediatric residents were going to do an evaluation to test Teeny's cognitive abilities and to see if she qualified for Special Instruction.

I worried because by Wednesday morning Teeny was really sick with exactly what Bee had. I wasn't sure she would be at her best for an evaluation and I was even less sure that the doctor would be thrilled to have a sick and feverish baby in her office. But I called first thing in the morning to let then know what was happening, and no one called back to cancel or reschedule so we went.

I was nervous. I had a little lump in my throat as we waited because this was it, the first evaluation of Teeny's cognitive ability capacity since the MRI. We had one before then, and she tested within the average range, but I needed reassurance. People tend not to believe the severity of Teeny's diagnosis because she doesn't "look" it. She has no facial characteristic that you might think someone with a brain injury would have. She doesn't make weird sounds or do anything out of the ordinary except look wobbly and unsteady when she moves. So I feared that the first evaluator, who saw her long before we got any kind of diagnosis, might have gone easy on her or not looked for specific things that she might have, had she known what she was really dealing with.

More than anything else, I want Teeny to be okay cognitively. I know I don't get to decide what happens to her, I know it's beyond my control. But I can't help trying to make little deals with this demon Cerebellar Hypoplasia in my head. I try to negotiate: "Fine, if she has to walk with a walker or with braces, fine fine. If she needs help learning, fine. If she doesn't become an Olympic gymnast or a brain surgeon, fine. But please, please don't let her be..." and I can't finish the sentence, even in my head. "You know. Please don't let her be that word that we can't say anymore. Please don't let her be that."

When we were called, we were led to a playroom that looked like all the other evaluation rooms we've seen so far. There was a little table and a few little chairs in the center and toys scattered around the periphery. The doctor, a thin, professionally dressed woman with a big diamond ring and a crisp British accent opened a closet door and got out the same rainbow colored mat we have at home and tossed a few toys on it. Teeny was tired but interested. I sat on the mat with her to wipe her horribly runny nose, one hand on her back to keep her from falling over. There were two pediatric residents managing the paperwork, sitting awkwardly in two of the little chairs, clipboards balanced in their laps. We all chatted briefly about her diagnosis and medical history. I babbled on about the research I've been doing and about the various experts I've been in contact with and I asked her what she knew about cerebellar hypoplasia. She said very quickly that she was sure I knew more than she did specifically, but she talked about some other patients she'd evaluated and colleagues of hers we might see. Then she took off her heels and squatted down next to Teeny and started the evaluation. She picked up a plastic toy with buttons in the shapes of farm animals. Every button played a different song. She pressed the cow and it played Twinkle Twinkle Little Star. She pressed the duck, and it played Old MacDonald. She held it out to Teeny, who poked a finger at the cow, and after a moment, at the duck. "Good job, Teeny!" the doctor exclaimed, and took the toy away. She picked up a baby doll and a small plastic bottle and offered them to my daughter, who took the bottle and held it to her own mouth right away. A few seconds later she took the baby doll into her arms and, to my amazement because she's never played with a baby doll before, she held the doll to her chest and offered it the bottle. A collective Awwww rose up from all the adults in the room, who, for all their impressive specialties, board certifications and letters after their names, were still not impervious to the cuteness and charm of my little girl. The doctor leaned in to one of the residents and murmured, "Give her full credit for that one."

And so it went, for nearly an hour and a half. She pulled out picture books and asked Teeny to point to specific things: cat, apple, car, baby. She gave her a toy and asked for it back. "Give me?" she asked, again and again. Teeny looked at her blankly. She procured a set of plastic cups and offered them to my girl, who grabbed them and happily banged them together. The doctor was trying to get her to transfer them from one hand to the other, which I knew she could do easily, but she was much more interested in making noise so she kept banging them together and squealing with delight. After a moment, she dropped one and transferred the other from one hand to the other. "You did it!" cried the doctor, who suddenly seemed as invested as I was in seeing Teeny succeed. She handed her a few small objects - Lego pieces, a plastic coin - and asked her to put them in the cup. "Put in?" she asked, in her sharp British accent. Teeny has been practicing this one at home every day but with bigger toys and bigger containers, so she had trouble at first, but she kept at it until she got them all in. "Look how hard she's trying!" the doctor said, and I heard the admiration in her voice. "She just doesn't give up, does she?" Nope, she sure doesn't.

As we went through the rest of the test, the doctor asked me a zillion questions about what Teeny can and can't do. She asked some of the same questions everyone asks: Does she gag when she eats? (no) Does she fuss in the bath? (no) When did you first notice something amiss? (right away) Any documented history of learning disabilities? (no) Can she play peekaboo? (yes) Feed herself with her hands? (yes) With a pincer grasp? (sort of) With a spoon? (no) Does she wave hello and goodbye? (yes) Nod her head yes? (sometimes) Do any sign language? (yes) Look around for her sister when you say "Where's Bee?" (no) Have any words? (yes) Say Mama? (no) She can't scribble, can she? (Oh, yes, she can!) And so on.

Then she put Teeny on her back and started stretching and pulling her to evaluate her tone. The cognitive part of the test was over, and my baby was exhausted. After two minutes of being handled, she began to protest. I took her in my arms and offered her milk; she was asleep in thirty seconds.

I wasn't going to waste any time though, so I pulled out my notebook and asked some questions of my own. I asked first about her overall cognitive ability, and the doctor said that even without adding up the scores of the tests we'd just done, she was confident that Teeny was normal and that her tests would all be within normal limits. I thought about the bargain I'd been trying to strike with the demon in my head and I needed more clarification. I had to know. So I said "You're telling me then, that she isn't, you know... retarded?" She looked at me quickly and said "Well we don't say that anymore, at least not clinically." And then under her breath she added, "Though we do still say it colloquially."

I waited.

"No," she said, "I definitely don't see any signs of that in Teeny."

She did say that her scores and her cognitive ability itself would be affected by her significant motor delays. For example, she said, you can tell she knows that she's supposed to stack these blocks, and she wants to do it, but she can't physically. This is very frustrating for Teeny and the longer her motor skills are behind, the more likely her cognitive development will be slowed too. We had heard the same thing from the psychologist who did her first developmental evaluation, so I wasn't surprised. For this reason, the doctor continued, she would be recommending Special Instruction. Not because she needed it developmentally, but because it could only help her, based on her medical diagnosis. "But EI will see from the scores that she doesn't really need it," she warned, "so you may not get much." This was the same warning we got from the speech evaluator, who recommended speech therapy on the same basis. I nodded, understanding that this was the best kind of bad news a mom can get, and said we'd just see what the EIOD thought.

Then I asked about autism spectrum disorders since I know they are highly associated with cerebellar hypoplasia. I barely got the question out when she cut me off. "No." She said. "But wait, I've read that--" "No!" She said again. "That is one thing you do not have to worry about." And she listed ten things about Teeny that proved to her that she was absolutely not on the spectrum. "But I read that you can't even tell until kids are two or three sometimes--" I started again and again she cut me off. "No. Just, no." I smiled, totally relieved, and went on to my next question. She sat on a tiny chair, one leg crossed over the other, and listened. She answered everything patiently, gave me her medical opinions, talked about other patients she'd seen, referred me to other experts, and was generally very absorbed in what we were doing until all of a sudden something somewhere beeped and there was a rush of iPhones and watches and shuffling of papers and they were late for their next meeting. I collected all Teeny's wadded up tissues and our bags and that was that.

I felt great after that. Christmas had come early for me. My daughter had a chance at a regular life. She was cognitively normal. The rest we could handle. I did a happy dance and told everyone who would listen. I even lifted my do-not-discuss-at-work ban. I got more and more focused on her therapies and getting her all the services we could cram into her increasingly busy schedule. But Teeny got sicker and sicker. This was the first week of her increased PT and OT and I hated to have her miss a single session, especially after hearing again that getting her motor skills up to where they should be is the best way to help her cognitively. So I tried to push her through her therapies, but she just wasn't having it. During one PT session, she wailed the entire time. The PT looked at me helplessly and said, "I think she's had enough." I glanced at the clock and opened my mouth to protest. After all, we had ten minutes left! But Johnny took me aside gently and said, "Aimee, look at her. We have to stop." I looked at her. The poor girl had glassy, bloodshot eyes and a runny nose. in the past 48 hours, her fever had been up and down. Her voice was hoarse from coughing and more than once she'd coughed until she vomited. He was right. I cancelled her sessions for the rest of the week. Johnny propped her up on her boppy in front of Sesame Street and finally, she slept.

And slept.

On Thursday she was perkier. I pronounced Bee well enough to go to school and Teeny still unable to do her therapies but well enough to attend Bee's classroom's holiday event. I had a meeting I couldn't reschedule, so I had to miss it, but I think they had a lot of fun.

By Friday, it was my turn to be sick. And once the symptoms hit me full-force, I felt terribly guilty for pushing my baby to perform. This cold was a bad one, and Teeny definitely had it worse than Bee or me. But sick or otherwise, I'm still smiling today. Thanksgiving, usually my favorite holiday, was marred by the news of the diagnosis, and I was sullen and resentful and not in the least big thankful. Now it's settled in somewhat and while I'd still trade it away in a heartbeat, I am getting better at taking things one day at a time, preparing for the worst but hoping for the best. And all the while, knowing that Teeny's running this whole thing. The developmental pediatrician said that determination is a cognitive skill. So if that's true, then really, she's got a lot going for her. I think about this over and over. It's the one thing that every single therapist, doctor, counselor, nurse, friend and family member says about Teeny. She doesn't give up. She tries so hard. She's really so motivated.

So I am taking my cues from my daughter. Remembering that makes all that we're doing worth it, and there is still so much to be done. In the past two weeks we've found a speech therapist who will come to us at hours that work for Teeny's schedule, so even though the speech hasn't even been approved by Early Intervention yet, we'll be ready to go when it is. Now we're on the lookout for Special Instructors. Recently, Teeny and I have gone gluten-free to see if this helps her in any way. I've packaged up still more copies of the MRI images and now the ultrasound images from my pregnancy as well, to have them looked at by the many experts helping us. The pile of books and articles by the bed is growing and our savings is dwindling. My spreadsheet has more tabs. We made more appointments: next we're seeing a physiatrist and a geneticist. We rearranged our holiday travel so she would miss fewer therapy sessions, and our family understood. And every day we brush, we swing, we open our door to one therapist after another. It doesn't slow down. But we do it. Wouldn't you?

So as we wrap up this terrible, awful, no good year, we're feeling cautiously optimistic. And after so much sadness, Teeny, Bee, Johnny and I are ready for Christmas tomorrow. Despite all we endured in the past few months, we enjoyed Hanukkah and have been busy since, trimming our tree, listening to Christmas music on the radio, wrapping gifts, sending cards, wearing fuzzy socks, and shopping for (gluten free, vegan, organic) ingredients for sugar cookies and other holiday goodies. We're thankful to all of our wonderful friends and family who have been there for us even when we weren't up to talking. We love you and we wish you a wonderful 2013.

perfect...minus you being sick.

ReplyDeletewish I was elegant with words here but

Perfect

Is what comes to mind.

Xxxx

Oooo

missy

5291BD21BB

ReplyDeleteBeğeni Satın Al

En İyi Takipçi

Instagram Takipçi Kazan